What if I Forget How To Speak a Language?

Imposter syndrome as a language learner

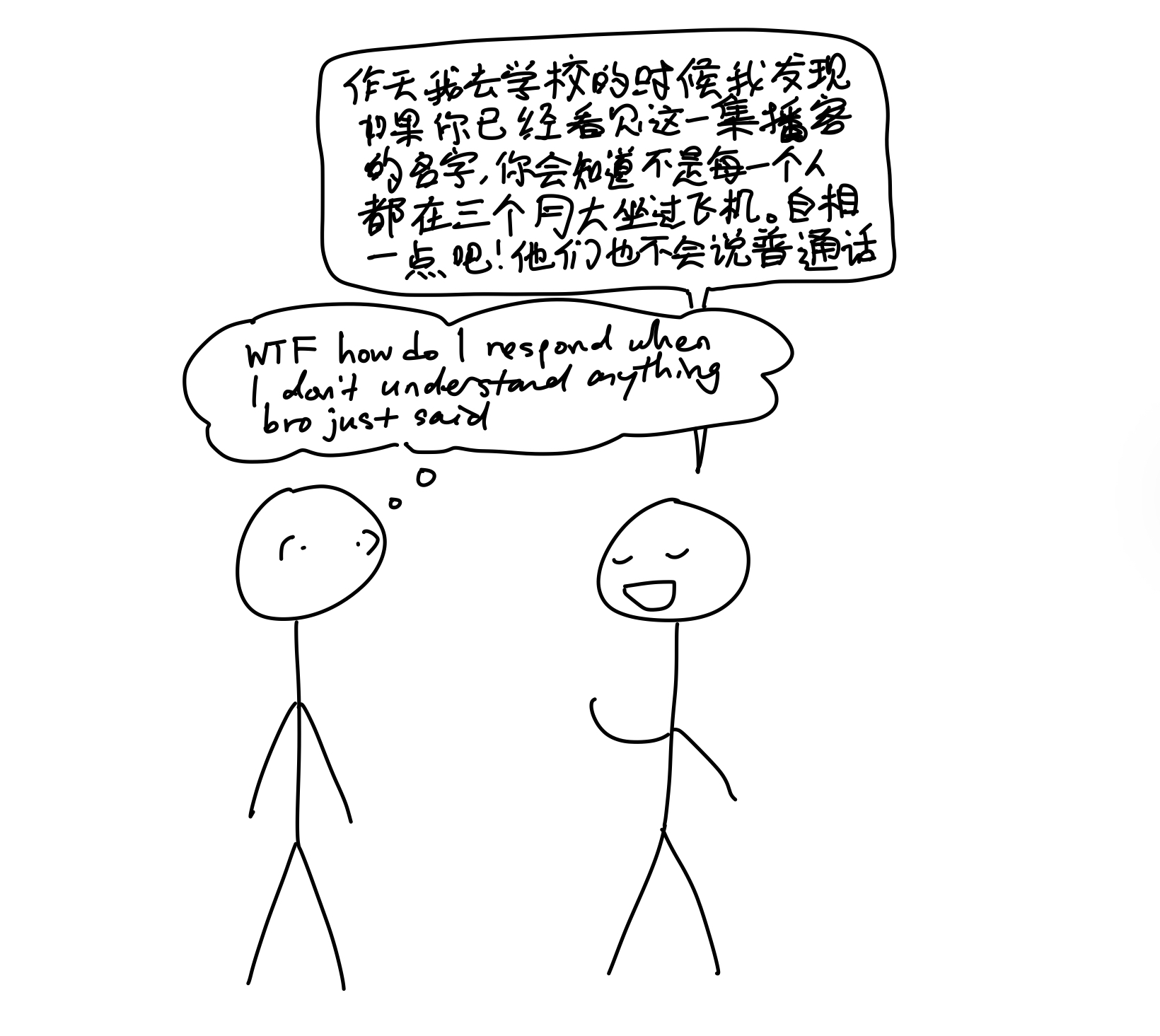

My mind when imposter syndrome kicks in.

Last night, I called my parents. I was telling my dad about a recent interview, how one of my interviewers was a senior in college, when he asked me an unexpected question. “Where did you learn the word 大四?” 大四 (dàsì) translates to “senior” or “4th year” in university. I told him I picked it up from a student-run music club where everyone was either an international student from China or grew up in America speaking Chinese. I could hear his smile through the phone as he explained that he only asked because he was surprised that I knew this colloquial piece of vocab. He and my mom never used it in conversation with me, and the Saturday Chinese school they put me when I was little didn’t teach colloquial language.

My parents grew up in Fuzhou, China. In their twenties, they moved to Japan, where my father attended graduate school and got a job. Then, before I was born, they relocated to California in the U.S. because they wanted their children to have more opportunities in life. I speak to my parents in Mandarin instead of English whenever I can, because conversations with them are one of the few opportunities I have to practice the language.

Impressing my dad boosted my confidence in my bilingualism a little bit, but after hanging up the phone, I still had that nagging feeling I always have that someday I’ll forget how to speak Chinese. Most days, I speak English with my classmates, hear English at school, and read English while studying. When I expressed this fear to my mom, something she said stuck with me. Don’t stress about this, okay? Chinese is like a native language for you, so you won’t forget it.

While it is true that I started learning Chinese from when I was a baby, I always felt like English was my native language and Chinese was my second one. It wasn’t until my mom reassured me that I wondered, Is it possible to have two native languages? Turns out, the answer is yes. If you learn two or more languages from a super young age, then all those languages can become part of your native language library.

Despite my mom’s kind words, I still feel insecure about my Chinese skills. Part of the reason is the feedback I’ve received from native Chinese speakers I’ve met at university. Almost all of them point out that it seems like Chinese isn’t my mother tongue. It does no good to compare my Chinese speaking ability, who grew up in the U.S., with that of someone who grew up in China, and yet I find myself comparing anyway. Before university, I never even knew that the difference between my Chinese and that of a native speakers was so different. At first, I felt disappointed in myself and my apparent lack of fluency. But now, this finding fascinates me and motivates me to absorb as much of the language as I can so that I can comfortably conversate with a native Chinese speaker without leaning on Chinglish (mixing Chinese and English).

Today, I casually learn Chinese in my free time by listening to podcasts, consuming Chinese dramas and music, and occasionally brushing off my reading skills with LingQ. Some of my favorite Chinese learning podcasts are Dashu Mandarin and TeaTime Chinese, which I usually listen to on long commutes or at the gym. My favorite Chinese drama ever is Go Ahead (以家人之名), recommended to me by a friend I met in an Intro to Cognitive Science class. I find LingQ, co-founded by polyglot Steve Kaufmann, a helpful app for listening and reading any language I’m learning.

If you are learning Mandarin Chinese, good luck on your language-learning journey. If there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that trusting your abilities, being willing to make mistakes, and finding beauty in the language are the three most important factors for succeeding at reaching fluency in a new language. One day, you’ll look back at all your progress and that sense of accomplishment will be priceless. Until then, keep doing what you do. Don’t worry too much about the right method or watching every “How to learn a foreign language” video on YouTube. Nothing is a waste of time. Learning what not to do can be just as valuable as learning what is right to do.