The Advantages of Being a Late Bloomer

Lessons from Hidden Potential by Adam Grant

Cover of Hidden Potential by Adam Grant. Credit: me.

Adam Grant, an I/O psychologist and professor at The Wharton School, uses compelling anecdotes and evidence to dispel myths about talent and hard work in skills-based activities such as sports, music, arts, and business. Here are my top three takeaways.

1. “It’s not about where you start. It’s about how far you go with what you have.”

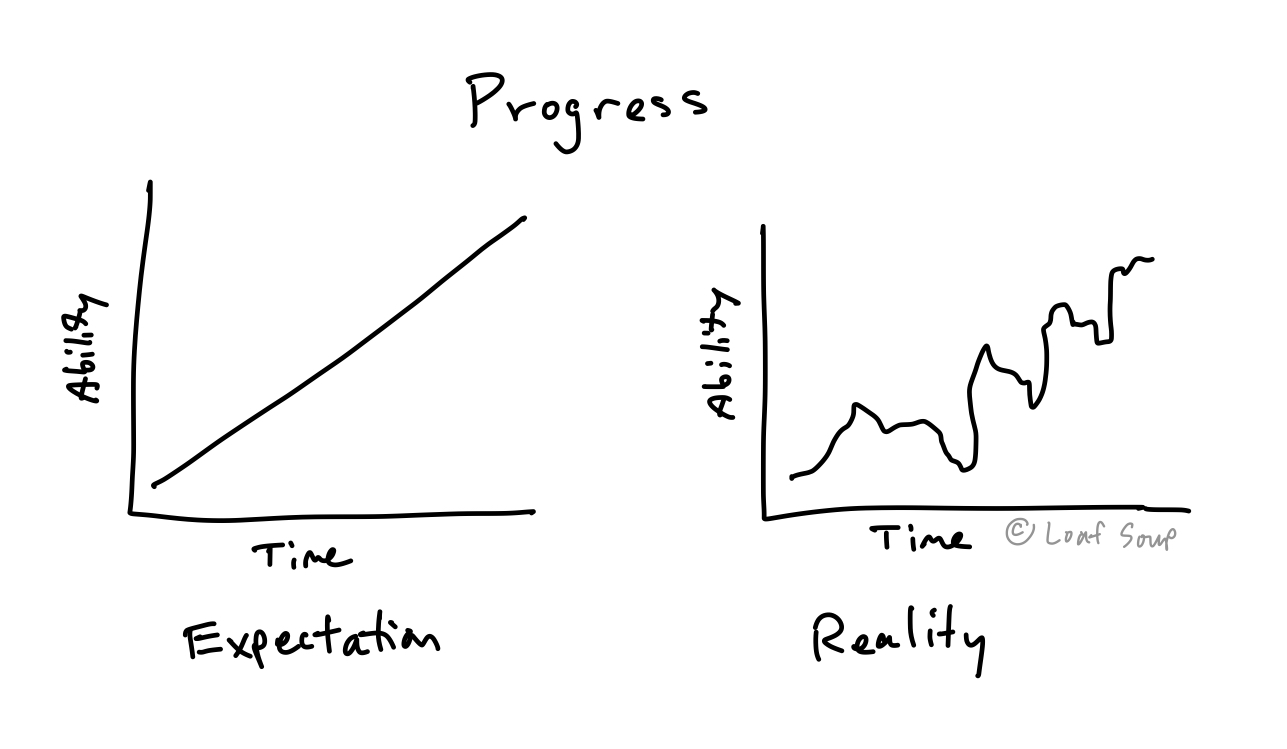

This lesson reminds me that it’s okay to get stuck. Setbacks and frustrations are all part of a long-term learning process. If anything, failures can become your superpower.

Progress is rarely linear.

Just look at Marin Alsop, the first conductor ever to win a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship. She failed Juilliard’s conducting auditions three times. A couple of years later, after having started her own orchestra and continuing to play violin, she got to meet famous conductor Leonard Bernstein and became “the first woman to ever conduct a major American orchestra.”

“I learn more from failure than I do from succeeding."

The first time I watched Marin Alsop conduct was through this legendary video of 18-year-old Yunchan Lim absolutely destroying Rach 3. Listening to this still gives me chills.

2. Embrace wabi-sabi (the beauty of imperfection)

Experts aren’t “more perfect” than beginners, because perfection doesn’t exist. Often, experts simply understand which imperfections are acceptable and which aren’t.

Done is better than perfect. Aiming for “good enough” is better than aiming for perfection, because perfection doesn’t exist and you’ll only drive yourself insane in the process.

3. Incorporate deliberate play into your routine

“There is no boring in our workouts.” This quote from Stephen Curry’s personal trainer, Brandon Payne radically changed the way I think about practice.

Deliberate play transforms rigid practicing into games, challenges, and exploration. For instance, Stephen Curry’s trainer Payne would make Curry play shooting games with clearly defined objectives like “score X hoops in Y minutes.” Musicians benefit from a daily dose of deliberate play too, when they give themselves the freedom to explore their instrument and its infinite possibilities.

Reflecting on my experiences as a music student, one main reason why I wouldn’t want to practice on certain days was boredom. Whenever I didn’t feel engaged with the material I was practicing, I lacked motivation and the desire to improve.

Taking piano lessons as a kid, teachers often told me to aim for perfect technique and sound. While I understand their well-meaning intentions, this guideline made me feel restricted, like I couldn’t make one wrong move while practicing. Sometimes I even felt anxious about practicing. What if I practice wrong and lose progress? The pressures of upcoming competitions and auditions amplified my fear of “going backward.”

Now, as a guitarist, I find that I have the most fun when I let myself try random ideas and explore the fretboard. While good technique and sound are crucial to master, fostering a love for the instrument and its music is just as important. Today, instead of viewing it as drills and clear-cut tasks, I approach practice as a time to get to know an instrument and all of its capabilities.

Bonus takeaway: Why late bloomers take the cake

Contrary to popular belief, late bloomers have advantages over early specializers. While the latter tends to make more money at the start of their careers, late bloomers tend to last longer in those careers, catch up salary-wise a few years later, and do better at the job.

We’re trained look up to the 20-year-old prodigy who graduated from med school before everyone else but don’t consider what likely comes after that: burnout, disillusionment, and changes in career path. The 40-year-old parent who graduated from med school with two kids, four past jobs, and experiences dabbling in music and philosophy might make a better doctor because she has more overall experience in life and other priorities that make her more resilient.

As Simone Stolzoff writes in his book The Good Enough Job, people can run into trouble when they tie their entire identity to work. It’s healthier to have multiple identities—runner, parent, friend, bookworm, basketball player, fossil collector, oboe player—than to gamble your entire personality on a job that your boss can take away from you at any moment.

When people see that 5-year-old violinist tearing apart Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E Minor, they get discouraged. I’ll never get to that point because I’m too old. Maybe that’s true. But take a look at these examples.

Red Garland, the American jazz pianist who played with famous trumpeter Miles Davis, started learning piano at age 18 after dabbling with clarinet and alto saxophone. Jasmine Chen, the Shanghainese jazz singer in Crazy Rich Asians, started studying vocal jazz in college; before then she didn’t know jazz existed. Duke Ellington, one of the greatest jazz pianists, "shunned music lessons as a kid" in favor of baseball and painting.

Closing remarks

I hope more teachers, coaches, and creative minds read Hidden Potential. I read the book during a rough patch, and it encouraged me to see my struggles for what they are: growth.

Hidden Potential also sparked my interest in Industrial/Organizational Psychology (I/O). As my school year starts this week, I hope to learn more about I/O through a social psychology course I’m taking this fall semester.