Lessons from The Psychology of Money

“Nothing is ever as good or bad as it seems.”

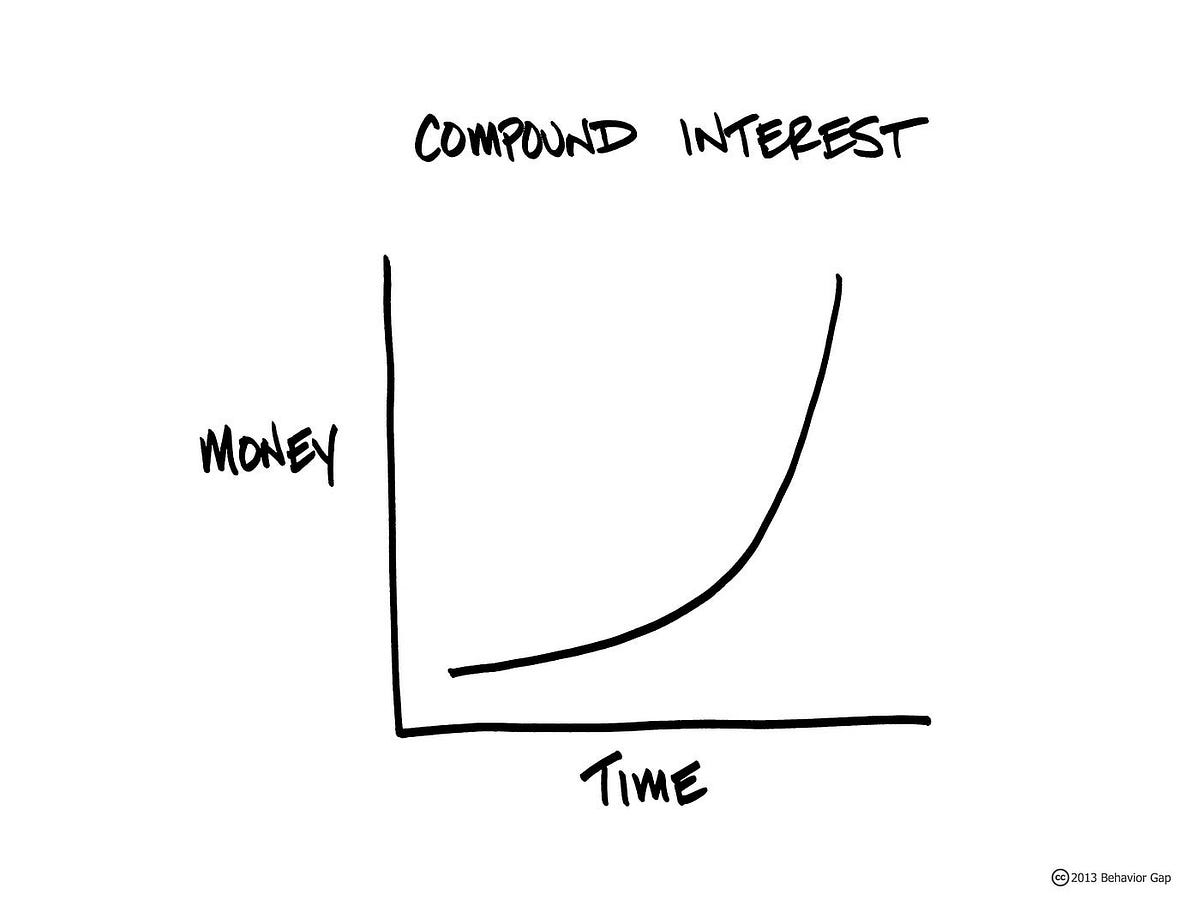

Credit: Behavior Gap

The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel is more than an informative nonfiction book about the nuances of managing one’s money. It’s also an enjoyable read full of life lessons and eye-opening perspectives.

1. Perspective is everything

Person A has 100 million dollars in the bank, but isn’t satisfied. They want more—more houses, more cars, more Gucci belts, more everything. So they spend and spend until they’re bankrupt. Yes, they were rich, but they aren’t rich anymore.

Person B has 1,000 dollars in the bank. Their income is modest, and they save 10% of every paycheck, putting it into a high-yield savings account or investing it into the S&P 500. When they get a pay raise, they stick with their modest lifestyle without making unnecessary upgrades. Fast forward 40 years, and Person B has substantial retirement savings to take life easy, support their family, and do whatever they want with their time.

Who has it better? Person B, because they learned what “enough” is for them. In contrast, Person A struggled to resist greed and made some unskillful decisions. It’s not that buying houses, cars, and Gucci belts is inherently bad. It’s about understanding that only you can define what is enough for you, and if you don’t define it, that can bite you in the [redacted] in the future.

2. “Nothing is ever as good or bad as it seems.” (My favorite lesson from the book.)

Housel talks about this in the context of successes and failures. I like to think about it in the context of “negative” experiences.

Housel describes how a person can strike it rich because of luck and then lose it all because of poor financial decisions. The “good” doesn’t seem so good anymore once you learn that it was so fleeting.

My take is similar, but a little different too. I make mistakes. You do too. Sometimes, not getting what you want can be a blessing in disguise.

Take the example of a breakup. Of course, a breakup is painful. But maybe it’s an opportunity to get more time back, focus on yourself, rediscover what you love about life, and ultimately find someone better for you.

Same goes for any challenge in life. Rejections, losses, and unwanted circumstances are only as bad as we make them out to be.

3. What works for Person X may not work for you, and vice versa.

Person X is single, unmarried, and has no kids. She writes for a finance column at ABC Magazine. Her priorities are following stock choices with high volatility (meaning the price of the stock has lots of fluctuations in price in a short time) and advising day traders.

Let’s say you, on the other hand, are married with three kids. You’re thinking about long-term growth of your savings. You and your spouse need to retire, and your kids need to afford college.

Think about you vs. Person X. Obviously, Person X’s advice likely has no bearing on your financial decisions. Yet many fall into the trap of following online financial advice without considering the source of that advice. That’s why it’s important to consider your goals first and foremost, before deciding on what advice to follow.

Same applies for you vs. your past self. Goals change over time. You aren’t the same person you were 5, 10 years ago. While an expert like Warren Buffett is a prime example of how sticking to one consistent goal pays off, sometimes life throws unexpected curveballs at you. In those cases, it can be smarter to adapt to change rather than stubbornly stick to an arbitrary rule.

It’s also important to understand that financial decisions aren’t made in a vacuum. Money matters are emotional matters. If we’re thinking about things we need and want, like food and fun, of course emotions are involved. Housel argues that this is why money is more than just accounting—it’s also highly connected to psychology.